Since the UK election, excitement about a market surge has been palpable. But who will benefit and who will lose?

By Nathan Brooker.

Since the UK election, excitement has been palpable. But there are still turbulent times ahead.

Simon Rowell is thrilled with his new purchase. Last week, he picked up the keys to a two-bedroom flat near Clapham Junction station in south-west London, which he intends to rent out for about £2,500 a month. “I’m one of the dying breed of private buy-to-let investors,” he says.

Rowell, creative director for Bannenberg & Rowell, a superyacht-design company, predicts the London property market will pick up this year, so he has snapped up what he thinks will be a good investment before it is too late. The flat cost £700,000 — just £2,000 more than its sale price in January 2017, when it was new. “That represents completely flat asset appreciation from the seller’s point of view,” he says. “I reckon that doesn’t last very long in London.”

Many property agents agree. Since the Conservative party won the general election in December, some have barely been able to contain their excitement at the prospect of a 2020 surge in prices and transactions in the UK capital.

“I went from despair to elation in a matter of hours when the results were announced,” says Trevor Abrahmsohn of agents Glentree Estates, which specialises in homes for wealthy buyers. “This could be a golden year.”

Agents are confident partly because the Conservative majority in parliament has released the Brexit logjam, but mostly because the Labour party, led by Jeremy Corbyn, did not win. Most agents were convinced that a Labour government would have targeted the UK’s luxury property market, with wide-ranging reforms to taxation and changes to laws for landlords.

Now, UK house prices are expected to rise in 2020. Savills is predicting 1 per cent growth; Strutt & Parker says 4 per cent. Camilla Dell of buying agents Black Brick thinks these forecasts are too conservative. She says prices for London’s best luxury homes could rise 10 per cent in 2020.

“The attitude of sellers has already changed,” says Dell. “They have become much more confident and are likely to take a much firmer line on offers.”

The optimists were buoyed last week when Cheung Chung-kiu, the Chinese property magnate, agreed to pay more than £200m for a mansion on Rutland Gate in Knightsbridge, a price that makes the property the most expensive sold in the UK. If agents’ predictions are right, which category of buyers stands to benefit — and which stands to lose — from a London property market surge? The FT asked experts and buyers what could happen over the next 12 months.

Luxury estate agents have described the record-breaking Rutland Gate sale as evidence that London’s prime property market is recovering — and holds its appeal — after years of falling prices and low sales figures.

“A big sale like that is emblematic of the turn in fortunes that we have seen in the market since the election,” says Liam Bailey, global head of research at Knight Frank. He says the number of exchanges his agency dealt with in prime central London in December was the second-highest monthly total since April 2014, when the market was booming.

Marc von Grundherr, a director at Benham and Reeves, which specialises in selling London property to overseas investors, sets the scene: “After the election, we had people who I hadn’t spoken to in a couple of years ringing up, saying: ‘Marc, let’s really look now — what can I buy?’” In the past four weeks, von Grundherr estimates that 200 of his clients called in to their offices worldwide, interested in buying London property.

Overseas buyers should find lower prices than in recent years — especially if they are US dollar buyers. According to Savills, the average price in prime central London has fallen by about 21 per cent since its peak in 2014. Once the currency exchange is factored in, dollar buyers today reap a discount of 38 per cent compared with five years ago.

They may soon get even more than that. Data published this week show the UK economy contracted by more than expected in November, adding pressure on the Bank of England to lower interest rates. While worsening economic conditions may not be good news for domestic buyers, the prospect of a rate cut sent the pound below $1.30 on Monday — and the weakened pound has attracted overseas buyers in search of a bargain.

But while some agents assume the recent flurry of prime London sales is an indication of renewed confidence, Neal Hudson, an analyst, says the uptick could be short-lived. He thinks that many of these buyers are from overseas and would have bought anyway, but are speeding through their purchase to beat an additional 3 per cent premium on foreign sales that was outlined in the Conservative manifesto.

“I suspect people will keep a close eye on when that policy is likely to be announced,” he says. What will happen after it is brought in? “The [prime] market will probably tank and we’ll go back to continued whingeing about high rates of stamp duty and people wanting it cut to get the market moving again,” he says.

“First-time-buyer numbers have been fairly static in London for the past few years, and that’s likely to continue,” says Hudson. “The problem is that house prices are still far too expensive for all but the luckiest of the lucky.”

Growing wages and falling prices have improved affordability, but not by enough. According to Nationwide, the average price for a first home in the capital was more than £401,000 at the end of 2019 — down from more than £419,000 at the beginning of 2018, but still 8.8 times the average London salary. The most unaffordable period for first-time buyers was the middle of 2016, when the average property was 10.2 times the average salary.

High prices have led many people to take advantage of the government’s Help to Buy scheme, which offers buyers of newly built homes an equity loan of 40 per cent in London. The scheme, set up in 2013, has supported more than 210,000 sales in England, but from next year it will be restricted to first-time buyers before it ends in 2023.

Or, at least, that is the plan. Many property experts argue that it will be difficult for the government to wean the market off Help to Buy, and the scheme will either be extended or another will take its place. The Conservative manifesto said the government “will review new ways to support home ownership” after Help to Buy is withdrawn. It also mentions “encouraging” a market for long-term fixed-rate mortgages, which could help reduce the size of the deposit that first-timers need.

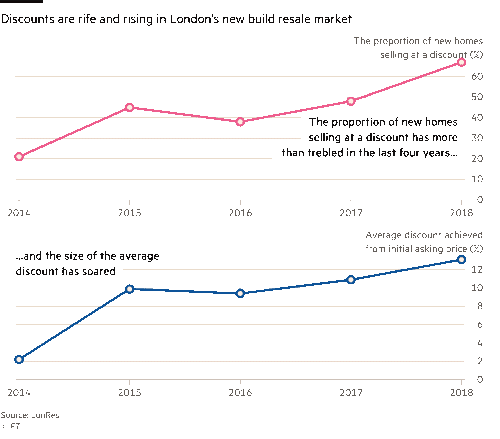

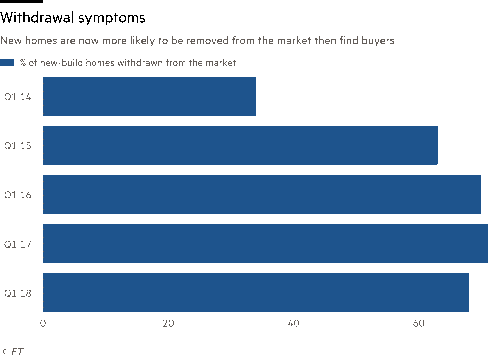

Rosie Smith, 34, who works for one of the Big Four accounting firms, has been looking for the right two-bedroom apartment in north London for several months. She has decided against using Help to Buy. “I very quickly decided not to do that when I realised how much more expensive the homes are,” she says. In October, research from Reallymoving, a price-comparison site for conveyancers and surveyors, calculated that first-time buyers using Help to Buy in London paid about 12 per cent more compared with those who bought new homes outside the scheme.

“[Our] research indicates that the attractiveness is enabling developers to charge more for homes with Help to Buy available and encouraging first-time buyers to pay over the odds,” the company says. The so-called premium comes on top of the already hefty premium new-build homes command over second-hand properties — and neither can be passed on when it is time to sell.

Smith is now looking for a two-bedroom flat in Islington or Haringey for about £450,000. “I’m in no real rush to move,” she says, “but I have lived in the same place now for seven years, and in that time, I have spent £70,000 on rent. I’d rather be paying off a mortgage.”

In August, Rebecca Stott set up Found It London, a buying agency specialising in first-time buyers. She predicts circumstances will improve this year. “Their main problem has been that there is just not enough stock on the market,” she says. A more positive market sentiment could lead to more homes up for sale.

Furthermore, changes to stamp duty for overseas buyers (as outlined in the Conservative manifesto) and the complete withdrawal of tax relief for landlords (which will come into force in April) will mean first-time buyers face less competition.

“There are always opportunities out there,” says Stott. “You just have to look for where the pockets of value are.” Stott recommends hunting in areas a little further away from Tube stations, for example, and — while this is not always easy — picking the right sellers. “People selling now who bought three or four years ago are struggling to get the price they paid. But find the people who bought 10 or 15 years ago [and] there’s your opportunity.”

Government policy tends to focus on helping first-time buyers, which means those hoping to trade up to a bigger property are often overlooked — and there is little in the Conservative manifesto to suggest this will change.

“Second-steppers are a largely forgotten segment of the housing market,” says Lucian Cook, director of residential research at Savills. “In London especially, their numbers have got pretty low.”

According to data from UK Finance, in the year to September there were 26,780 mortgaged movers in London — people who already have a mortgage moving to another property. That figure is more than 18 per cent lower than the 10-year average. The decline in mortgaged movers is a national phenomenon. According to data from Zoopla, in 1988 the average UK household moved once every 8.63 years; in 2017, people moved once every 23 years — and in London, once every 26.5 years.

London’s second-steppers have been held up by the widening gap between the prices of flats and houses. In October, the average gap between a flat and a terrace house in London was £94,000, according to Land Registry data. In October 2009, it was just £30,000.

Mortgage regulation has made it harder to trade up, says Cook. Currently, regulation limits lenders and stress-tests applicants’ affordability. “A lot of people are sitting on a pretty decent pile of equity but are unable to bridge the gap to the next step on the ladder,” he adds.

While the Conservative manifesto mentioned encouraging a new market for long-term mortgages to help first-time buyers, it is not clear if they want to relax the amount a person can borrow as a multiple of their salary — which is what ultimately limits second-steppers. And at this point, it is too early to tell if regulations will be relaxed when Andrew Bailey takes up his role as the new governor of the Bank of England in March.

“For most second-steppers, it is their need for more space that underpins their need to trade up,” says Cook, “and so many are going to have to relocate to cheaper markets — either cheaper places within London, or by moving out to the commuter belt.”

Gabriel Ng, a 27-year-old software developer, moved his young family from a two-bedroom flat in Barking to a four-bedroom house in London Square, a new development in Orpington, on the outskirts of south-east London. “We wanted a bigger home and better amenities close by,” he says.

Life will be tough for buy-to-let investors in 2020. According to research by Richard Donnell, director of research at Zoopla, the number of mortgaged investors buying in London is down more than 60 per cent compared with 2015.

“Everybody is having to adjust to a completely new landscape,” he says. In 2016, the government made it more expensive to buy rental homes by adding a 3 per cent stamp-duty premium to the purchase of additional properties. In 2017, it started withdrawing the tax relief that landlords could claim back. Before then, UK taxpayers renting out a property with a buy-to-let mortgage could deduct all mortgage interest payments from their tax bill, meaning they only had to pay tax on profits, not turnover. Because many landlords opted for interest-only mortgages, that was a substantial saving. But from 2017, that relief was phased out by the previous Conservative government until April this year, when they will not be able to deduct anything.

Meanwhile, slowing house-price growth has reduced the potential for capital appreciation, and many fear the long-term impact of Brexit could affect rents if fewer companies and workers are attracted to the UK.

Donnell has compared the business case that investors would have faced in 2016 with today. Then, the average amount spent on a rental property in London was £437,000 with a gross yield of 4.3 per cent. A lot of people are sitting on a pretty decent pile of equity but are unable to bridge the gap to the next step on the ladder Lucian Cook, director of residential research at Savills But at that time, if investors had assumed rents would have risen 3 per cent per year, and house prices would have risen 5 per cent (in 2016, they actually rose about 10 per cent, so 5 per cent would have felt pretty conservative), then they could have calculated their internal rate of return (IRR) at 7 per cent over 20 years.

Today prices are higher, with an average spend of £476,000, and yields are a little higher at 4.4 per cent, but with more modest predictions for house price and rental growth (about 2.5 per cent per annum for both) then their IRR falls to 4.8 per cent over 20 years. “This drop in return explains why we’re seeing a drop in investors buying in London,” says Donnell.

The outlook for rental returns outside London are better — Donnell calculates the IRR in the north-west of England to be 8 per cent, for example. Nevertheless, London retains its appeal: “If you want strength and stability of cash flow, then of anywhere in the UK, London is still the best place to get it,” says Donnell.

“In the analysis we have just done, the average rent in London is £1,800 per month; in Manchester, the typical investor is only getting £720.”

A government survey released this month found 45 per cent of landlords in England have only one investment property, and 44 per cent became landlords to contribute to their pension.

“What does every pension investor want? An asset that performs in line with earnings growth because that is what they’re losing when they retire,” says Donnell.

Sometimes, real life — rather than mere market sentiment — brings an overriding reason to buy a home. For Rowell, the landlord who has just bought a flat near Clapham Junction, the potential for his family to use the property in the future was a big draw.

“We have got teenagers,” he says. “On the basis that our kids hopefully will be young professionals themselves one day, this property gives us lots of options.”